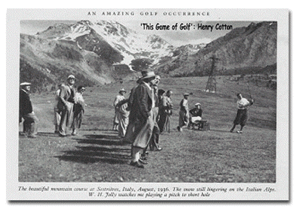

Joe Ezar was not on board the Queen Mary on that voyage. In that last week of August he was one of a small band of professionals who arrived in Sestrieres, the Italian winter resort 6000 feet up in the Alps not far from Turin.

Also in the party were Henry Cotton, German Open champion Auguste Boyer and French Open winner Marcel Dallemagne. They were there to play in the Italian Open, which Cotton was to win, but it was the performance of Joe Ezar that has entered the record books. Joe was playing better than he had on previous visits to Europe and even beat the almost invincible Open Champion, Alf Padgham, that year in a 36-hole match. Henry wrote of the ‘amazing golfing occurrence’ that I mentioned earlier, which happened during that championship.

In This Game of Golf, he told of Joe’s arrival at Sestrieres sporting a camel hair coat bound with leather, which he had bought in Berlin with prize money from the previous week’s German Open. (Marks could not be exported at that time). Although the weather was fine and very warm Joe played part of the tournament wearing the coat like a cape.

The Sestrieres course was quite short at around 6000 yards and Henry equalled the record of 67 twice on the first day and added a 68 to take a big lead, but it was the round that was to earn Joe Ezar second place, and a lot of lira, that made the news. He had already astonished the watching pros when he gave his trick-shot exhibition on the first evening, particularly the two putts he holed.

He put down three balls on the 9th green, at least 20 ft from the cup, and announced that he would hole one ball in three shots. Henry Cotton described what happened next: “Well, we all knew this green and this particular putt down the hillside, so we nudged one another and said, ‘what a hope!’ Well, the third ball went in. ‘What a fluke’, said we. Joe went to the front of the green, put the balls down again, and announced, ‘To hole the third ball’. The first ball was struck short, the second ball was wide and the third ball was in! This looked almost too deliberate to be a fluke, but there it was, two nominated performances, always difficult feats to attempt, particularly at golf, a game I know too well. Other spectators were equally amazed.”

All present were impressed, particularly the president of the club, a non-golfer, and when he handed Joe his fee he said that it was a wonder that, with his skill, he did not break the course record. Joe replied: “How much would you give me if I do break the record?” “One thousand lira for a 66”, said the president. “How much for a 65?” asked Joe.” “Two thousand lire” was the reply. “And for a 64?”, Joe enquired. “Four thousand lira,” laughingly said the president. “Right, I’ll do a 64,” said Joe and, on a cigarette packet borrowed from the president, he wrote down the hole-by-hole scores totalling 64.

In This Game of Golf Henry said that the president, Joe’s partner and several spectators testified that he shot the score as nominated, even pitching in from around 50 yards at the 9th for a 3 to keep to schedule.

Here, as you often find in accounts of incidents in golf, there is a contradiction. Under the Curious Scoring section in the Golfers Handbook it is stated that the predicted scores at the ninth and tenth holes were 3,4 and the actual scores were 4,3. Henry saw little of the round himself as he was out there scoring a 66 to take the title, but he did see Joe collect his 4000 lira from the president at the presentation dinner, when there was much debate about, in Henry’s words, “one of the most amazing occurrences I have ever known in the game of golf.”

Was it a colossal fluke or a combination of skill and luck? The fact that Henry’s two 67s and final 66 were the three other lowest by any of the players in the event makes Joe’s round all the more extraordinary. As I said earlier, if he had taken golf more seriously his name may well have been in the major championship lists, not just a seldom noticed entry under Curious Scoring.